There’s a questionnaire that I go through with my new customers over the phone, and in it I ask if forced appreciation is part of their investment strategy. Often I hear a response of “huh?”

Forced appreciation belongs mostly to the world of commercial real estate. It’s natural for the new real estate investor to gravitate towards residential because everyone understands it. We all live in a home and pay a mortgage or rent payment. Prices fluctuate due to supply and demand, and we understand this. What many don’t understand is that commercial property is the investor’s preferred real estate. Why do I say this? I thought you’d never ask…

Property prices are always truly decided by the buyer and seller. But market value can be determined by a property appraisal. Here’s where residential and commercial RE appear to come from different planets. Residential property is almost always appraised by comparable sales. In other words, the market value is whatever everyone else is paying in that area for that type of property in that type of condition. The purpose of residential property ownership is living space. So “type of condition” means the physical condition of the structure & its fixtures. Bank lending plays an important role in how appraised value and actual purchase price interact. Most residential property is purchased with mortgage financing. Residential appraisals are based on what others are paying for similar properties, and the lender ends up only lending if the purchase price of the subject property (which is the loan collateral) isn’t much higher than the appraised value. So, when you are in the market to buy or sell, you’ll generally need to buy or sell for a price close the the appraised value.

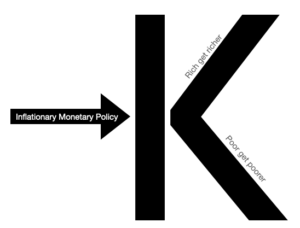

When investing, the two things that indicate the performance of your property owned are cash flow and gains or losses upon liquidation. In residential real estate, your gain or loss upon liquidation is determined almost entirely by what other people are paying for similar properties at that time. So what’s wrong with that? Well, for starters changes in lending will affect what people pay for properties. The actual price paid by the mortgage borrower is felt by the monthly payment. So if interest rates, insurance rates, or property tax rates go down then the buyer can comfortably afford to pay more for the residential property. If those expenses go up, the buyer won’t be able to afford to pay as much of a purchase price, and the prices will come down. Another effect we’re living with today is how flexible the banks are with their LTV and income/employment/reserves documentation. If the required down payment is small or zero, the buyer can then feel comfortable paying a higher monthly payment so they can and will pay a higher purchase price. That works both ways as well. The same goes for underwriting guidelines: If somebody who can’t prove much income (possibly because they don’t have much income) can obtain a large mortgage that was previously unavailable to them, then the residential real estate market is flooded with new buyers and the increased demand will increase prices. The result is that residential real estate ownership investment gains and losses are decided mostly by factors outside of your control: interest rates, mortgage rates, tax rates, and loan underwriting guidelines.

Commercial real estate, on the other hand, is cash flow real estate. Remember, we said residential appraisals are based on similar properties in similar conditions. With commercial, this is the same but different. The purpose of residential property is living space. The purpose of commercial property is income. So when an appraiser is concerned with the condition of the property, he’s really concerned with the income. The market value is usually based on income using the “cap rate” for that market.

So here’s how that works in action. You can’t control what other people are buying and selling for in a residential RE market because you can’t control taxes, insurance premiums and underwriting guidelines. Lack of control means risk. You can reasonably control the income of a commercial property.

Example:

Upon shopping for a commercial property (let’s say an apartment building), you find something promising: A 100 unit building with 70 units occupied. This means it has a 30% vacancy rate. The tenants are all paying about $500 per month. You realize it’s quite attractive once you discover that the average vacancy rate for apartment buildings in that area is 15%, and the average rent (as evidenced by a comparable rent schedule provided by an appraiser) is $600. The property management company isn’t on top of things, and they haven’t raised the rent along with the rest of the market. Closer inspection shows you that they aren’t very nice either, and they are famous for not responding to maintenance requests very quickly. Now this is a gem. Why?

- Because nobody wants to live there. The management is mean and slow to respond. You can replace the property manager with a company that is much nicer and offers quicker response to maintenance requests. This will retain tenants, improve reputation, decrease vacancy, and thus increase income.

- If the market rents are $600, raise the rents to this point to be competitive. This will immediately increase income as old tenants move out and new ones move in.

Let’s say the cap rate in the area is 10% (this is no longer the “standard” it used to be, but we’ll use it for simplicity). The current owner wants to sell, and the appraiser reviews the property and the financials, and it looks like this:

$420,000 Gross Annual Income ($500 rent x 100 units x 70% occupied x 12 months)

($60,000) Insurance Premiums

($55,000) Property Taxes

($20,000) Annual Maintenance

$285,000 Net Operating Income (NOI)

NOI ($285k) divided by cap rate (10%) = $2,850,000 market value

So you purchase the property for $2,850,000. You raise the rents and replace the property manager with one who is kind and responsive. Vacancy rates over time (say 36 months) are reduced to 15%. Now, when you get it appraised it will look like this:

$612,000 Gross Annual Income ($600 rent x 100 units x 85% occupied x 12 months)

($60,000) Insurance Premiums

($55,000) Property Taxes

($25,000) Annual Maintenance (a bit higher because of more use)

$472,000 Net Operating Income

NOI ($472k) divided by cap rate (10%) = $4,720,000 market value

What were your risks? The cap rate could have moved out of your favor. The market rent could have decreased which would either increase your vacancy or decrease the rent you charge. Now, realistically the risk of these factors eating too much into your profit is much lower than getting smacked upside the head by all of the uncontrollable factors involved in residential property ownership.

Is this above example feasible? Yes (although the example is uber-simplified). The trick here is in the pre-purchase evaluation of the property. You identified that the income could be easily increased due to current mismanagement. This, my friends, is forced appreciation [Cue the applause, somebody just profited over $1,500,000 in 36 months with a down payment of about $650,000]. This is only the appreciation (not the cash flow), and it created a 230% cash on cash return, or 76% annualized.

If you can’t find one this promising, adjust your numbers. You tell me what the return is if the property initially had instead a 20% vacancy rate and rents of $560 per unit. So now ask yourself what residential real estate investment strategy can provide that type of target return, control, and limited risk?